Confirm resistance through PCR-based methods targeting specific mutations in the gyrA and parC genes. This precise identification guides treatment selection, avoiding unnecessary antibiotic use.

Doxycycline and minocycline represent viable alternatives. Consider dosage adjustments based on patient factors like renal function and age. Monitor for treatment success using clinical symptoms and repeat PCR testing after a prescribed course.

For severe infections or treatment failures, consider combination therapy using doxycycline alongside azithromycin. This approach targets different bacterial mechanisms, potentially overcoming resistance. Always consult current treatment guidelines and adjust based on local antibiotic susceptibility patterns.

Proactive infection prevention remains key. Adherence to strict hygiene protocols, particularly in healthcare settings, significantly reduces transmission. Accurate diagnosis using specific laboratory methods is crucial for timely intervention and improved patient outcomes.

- Ciprofloxacin Resistance in Urinary Tract Infections (UTIs)

- Understanding the Mechanisms of Ciprofloxacin Resistance

- Mutations in DNA Gyrase and Topoisomerase IV

- Efflux Pumps

- Reduced Outer Membrane Permeability

- Risk Factors for Ciprofloxacin-Resistant UTI

- Diagnostic Approaches and Treatment Strategies for Ciprofloxacin-Resistant UTI

- Identifying the Resistant Organism

- Treatment Options for Ciprofloxacin-Resistant UTIs

- Monitoring Treatment Response

- Preventing the Spread of Ciprofloxacin Resistance in UTI

- Hygiene Practices

- Proper Sexual Health Practices

- Preventing Recurrence

- Healthcare Provider Communication

- Reporting Resistant Infections

- Understanding Antibiotic Stewardship

- Future Research

- Developing New Antibiotic Therapies

Ciprofloxacin Resistance in Urinary Tract Infections (UTIs)

Doctors increasingly encounter Escherichia coli (E. coli) strains resistant to ciprofloxacin in UTIs. This resistance significantly complicates treatment. Global surveillance data show resistance rates vary widely, exceeding 30% in some regions.

Understanding Resistance Mechanisms: E. coli develops ciprofloxacin resistance primarily through mutations in genes encoding DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV, the enzymes ciprofloxacin targets. Horizontal gene transfer, particularly plasmids carrying resistance genes, also plays a crucial role in spreading resistance.

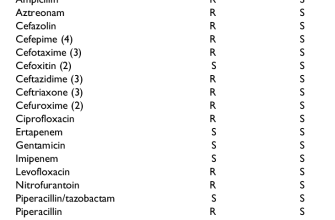

Impact on Treatment: Ciprofloxacin resistance necessitates alternative antibiotic choices for UTI treatment. These alternatives include nitrofurantoin, fosfomycin, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. However, resistance to these alternatives is also rising.

Diagnostic Considerations: Rapid and accurate identification of resistant strains is key. Culture and susceptibility testing remain the gold standard for guiding antibiotic selection. Molecular methods, like PCR, can detect specific resistance genes, offering faster results in some settings.

Prevention Strategies: Reducing antibiotic use is paramount. Appropriate antibiotic stewardship programs in healthcare settings, promoting responsible prescribing and reducing unnecessary antibiotic use, are crucial to limiting resistance development.

Future Directions: Research focuses on developing new antibiotics and alternative therapeutic approaches to combat resistant UTIs. This includes exploring new drug targets and exploring bacteriophage therapy as a potential alternative.

Conclusion: The increasing resistance of E. coli to ciprofloxacin in UTIs highlights the urgent need for responsible antibiotic use and the development of new treatment strategies.

Understanding the Mechanisms of Ciprofloxacin Resistance

Ciprofloxacin resistance in Uropathogenic E. coli (UPEC) and other UTI-causing bacteria primarily stems from mutations affecting two key targets: DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV. These enzymes are crucial for bacterial DNA replication and are the primary targets of ciprofloxacin’s action.

Mutations in DNA Gyrase and Topoisomerase IV

Mutations within the genes encoding these enzymes, *gyrA*, *gyrB*, *parC*, and *parE*, commonly lead to amino acid substitutions that directly impair ciprofloxacin binding. Specific mutations, such as Ser83Leu in GyrA, are frequently observed and strongly correlate with resistance. These changes reduce the drug’s affinity for the target, hindering its ability to inhibit DNA replication.

Efflux Pumps

Another significant mechanism is the overexpression of efflux pumps. These cellular pumps actively expel ciprofloxacin from the bacterial cell before it can reach its target. Increased expression of pumps like AcrAB-TolC significantly contributes to resistance, often in combination with target site mutations. These pumps are regulated by various factors, including the expression of regulatory genes.

Reduced Outer Membrane Permeability

Changes in the bacterial outer membrane can also limit ciprofloxacin entry. Alterations in lipopolysaccharide (LPS) structure or porin proteins reduce the permeability of the outer membrane, restricting ciprofloxacin’s access to its intracellular targets. These changes are less common as a sole mechanism of resistance but contribute significantly when combined with other resistance mechanisms.

Risk Factors for Ciprofloxacin-Resistant UTI

Prior antibiotic use, especially fluoroquinolones, significantly increases your risk. This includes both recent and past exposures. The longer your history of antibiotic use, the higher the risk becomes.

Hospitalization elevates your risk due to increased exposure to resistant bacteria in healthcare settings. Length of stay correlates with increased risk. Prolonged use of urinary catheters during hospitalization further increases susceptibility.

Specific infections, like those caused by Escherichia coli (E. coli), are more likely to develop ciprofloxacin resistance compared to infections caused by other bacteria. This is due to the prevalence of resistance genes within certain E. coli strains.

Certain demographics show higher rates of ciprofloxacin-resistant UTIs. Older adults and individuals with compromised immune systems are particularly vulnerable. Geographic location also plays a role, with some regions demonstrating higher rates of resistance.

Lack of adherence to prescribed antibiotic regimens contributes to the development and spread of resistant bacteria. This includes premature discontinuation or incorrect dosage. Complete the prescribed course as directed by your physician.

Underlying conditions, such as diabetes and kidney disease, can weaken the immune system and predispose individuals to antibiotic-resistant UTIs. Careful management of these conditions is important.

Diagnostic Approaches and Treatment Strategies for Ciprofloxacin-Resistant UTI

First, obtain a clean-catch urine sample for culture and sensitivity testing. This identifies the causative organism and determines its susceptibility to various antibiotics. Rapid diagnostic tests, such as urine dipsticks, provide preliminary results but are not sufficient for guiding treatment of resistant infections.

Identifying the Resistant Organism

Accurate identification of the specific bacteria causing the UTI is paramount. Common culprits include Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Proteus mirabilis. Molecular techniques may be necessary to detect extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)-producing organisms or other resistance mechanisms, ensuring targeted therapy. Antibiogram reports from your lab should detail the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) for various antibiotics, providing clarity on treatment options.

Treatment Options for Ciprofloxacin-Resistant UTIs

Treatment selection depends on the identified organism and its resistance profile. Consider alternatives like nitrofurantoin, fosfomycin, or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, depending on susceptibility results. For severe cases or infections caused by multi-drug resistant bacteria, intravenous carbapenems or aminoglycosides may be required. Always follow local antimicrobial stewardship guidelines for appropriate antibiotic selection and duration of treatment.

Monitoring Treatment Response

Regularly monitor patients for clinical improvement, including resolution of symptoms such as dysuria, frequency, and urgency. Repeat urine cultures after completing antibiotic therapy can confirm eradication of infection. Consider retesting if symptoms persist or relapse occurs. Prophylactic strategies, such as cranberry supplements or post-coital antibiotic regimens, may be discussed for recurrent infections.

Preventing the Spread of Ciprofloxacin Resistance in UTI

Finish your antibiotic course completely, even if you feel better. This prevents resistant bacteria from multiplying and spreading.

Hygiene Practices

- Wash your hands thoroughly and frequently with soap and water, especially before and after using the toilet.

- Practice good hygiene when cleaning yourself after urination or bowel movements, wiping from front to back.

Avoid unnecessary antibiotic use. Antibiotics should only be prescribed for bacterial infections, not viral ones. Discuss alternatives with your doctor.

Proper Sexual Health Practices

- Practice safe sex, including using condoms, to reduce the risk of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) that can contribute to UTIs.

- Limit the number of sexual partners to lower the risk of infection.

Drink plenty of fluids, especially water, to help flush out bacteria from your urinary tract. Aim for at least eight glasses a day.

Preventing Recurrence

- After a UTI, discuss preventative strategies with your doctor, which may include antibiotics or other treatments.

- Identify and address underlying medical conditions that increase UTI risk, such as kidney stones or diabetes.

- Consider cranberry supplements, although their effectiveness is still debated; consult your doctor.

Healthcare Provider Communication

Inform your doctor about all medications you take, including over-the-counter drugs and supplements. This helps prevent drug interactions.

Reporting Resistant Infections

If you are diagnosed with a UTI resistant to ciprofloxacin, report it to your doctor and relevant health authorities. This data helps track antibiotic resistance patterns.

Understanding Antibiotic Stewardship

Antibiotic stewardship programs aim to optimize antibiotic use, reducing resistance. Support these programs by following your doctor’s advice on antibiotic treatment.

Future Research

Developing New Antibiotic Therapies

Support research into new antibiotics and alternative treatments for UTIs, as this is crucial for managing antibiotic-resistant infections.