Amoxicillin is frequently ineffective against Enterococcus faecalis infections. High rates of intrinsic resistance mean alternative antibiotics are often necessary. This necessitates a targeted approach to treatment.

Consider E. faecalis’s inherent resistance mechanisms. These include reduced permeability of the bacterial cell wall and the production of beta-lactamases. Understanding these factors guides antibiotic selection. Ampicillin, a closely related antibiotic, also shows poor efficacy against many E. faecalis strains.

Before prescribing any treatment, always obtain a culture and sensitivity test. This informs the choice of the most suitable antibiotic, ensuring optimal treatment. Appropriate antibiotic stewardship minimizes resistance development and improves patient outcomes. Consult current clinical guidelines for updated recommendations on antibiotic choices for enterococcal infections.

Remember: Self-medicating is dangerous. Always seek medical advice from a healthcare professional for diagnosis and treatment of infections. Never rely on general information for specific medical guidance.

- Enterococcus faecalis and Amoxicillin: A Detailed Look

- What is Enterococcus faecalis?

- Amoxicillin’s Mechanism of Action: How it Works

- Enterococcus faecalis Resistance to Amoxicillin

- Clinical Significance: Infections Caused by Amoxicillin-Resistant E. faecalis

- Diagnosis of E. faecalis Infections

- Treatment Options Beyond Amoxicillin

- Alternative Antibiotics

- Combination Therapy

- Surgical Intervention

- Monitoring and Follow-up

- Preventing E. faecalis Infections

- Future Directions in Combating Amoxicillin-Resistant E. faecalis

- Targeting Biofilm Formation

- Combating Resistance Mechanisms

- Enhanced Diagnostics

- Combination Therapies

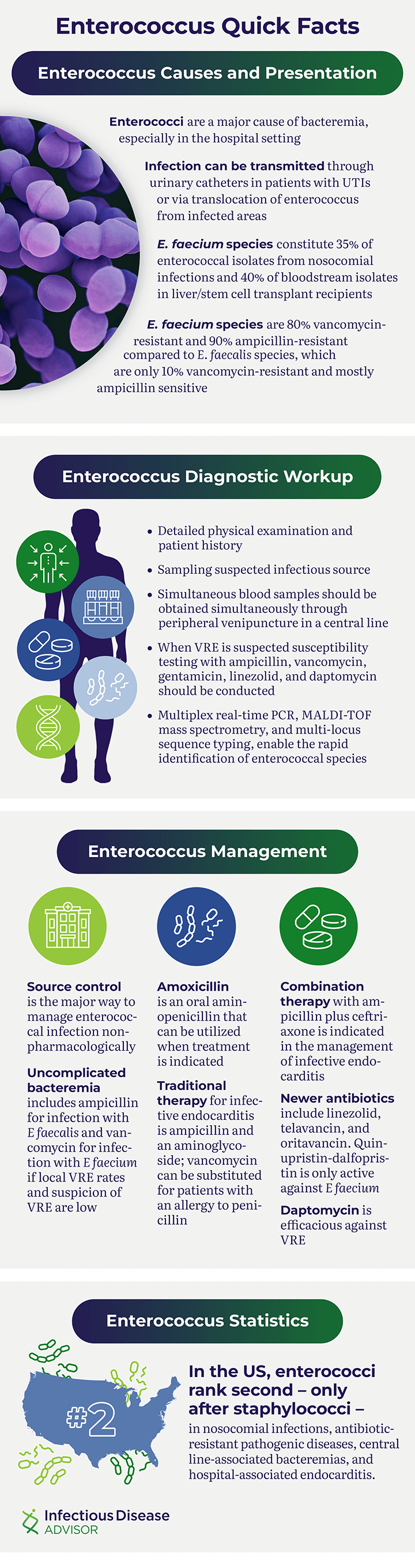

Enterococcus faecalis and Amoxicillin: A Detailed Look

Amoxicillin is generally ineffective against Enterococcus faecalis. This is due to the bacteria’s inherent resistance mechanisms.

E. faecalis frequently possesses intrinsic resistance to beta-lactam antibiotics like amoxicillin. This resistance stems from modifications in penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs), the bacterial targets of amoxicillin. These altered PBPs have a reduced affinity for amoxicillin, significantly hindering the antibiotic’s ability to inhibit cell wall synthesis.

Furthermore, some strains produce beta-lactamases, enzymes that directly inactivate amoxicillin. This enzymatic degradation renders the antibiotic ineffective. The prevalence of these resistance mechanisms varies geographically and within specific patient populations.

Consequently, clinicians rarely prescribe amoxicillin for E. faecalis infections. Instead, treatment strategies typically involve alternative antibiotics with proven efficacy against this resistant pathogen. These include ampicillin-sulbactam, vancomycin, linezolid, and daptomycin. The choice of antibiotic depends on factors such as the severity of infection, patient allergies, and local antibiotic resistance patterns.

Always consult a healthcare professional for accurate diagnosis and treatment of bacterial infections. Self-treating can have serious health consequences.

Laboratory testing is crucial for confirming the identification of E. faecalis and determining its antibiotic susceptibility profile. This allows for targeted antibiotic therapy, improving treatment outcomes and minimizing the risk of resistance development.

What is Enterococcus faecalis?

Enterococcus faecalis is a bacterium commonly found in the human gut. It’s typically harmless, part of our normal gut flora. However, it can become a serious problem if it enters the bloodstream or other parts of the body.

This bacterium shows remarkable resilience. It thrives in various environments, including those with low oxygen levels and high salt concentrations. This adaptability contributes to its ability to cause infections.

E. faecalis infections often occur in hospitals, affecting patients with weakened immune systems or those who’ve undergone surgery. Common infections include urinary tract infections, endocarditis (heart valve infection), and wound infections.

Identification: Laboratory tests, including cultures and susceptibility testing, are needed to confirm E. faecalis infection and guide treatment.

Treatment: Antibiotic resistance is a significant concern. While amoxicillin may be effective in some cases, other antibiotics, like ampicillin or vancomycin, are often necessary for more severe or resistant strains. Your physician will determine the appropriate antibiotic based on the infection’s specifics.

Proper hygiene practices, such as thorough handwashing, are crucial in preventing the spread of E. faecalis, particularly in healthcare settings.

Amoxicillin’s Mechanism of Action: How it Works

Amoxicillin inhibits bacterial cell wall synthesis. This is achieved by interfering with the final stages of peptidoglycan formation, a crucial component of the bacterial cell wall.

- Specifically, amoxicillin binds to penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs).

- These PBPs are bacterial enzymes responsible for cross-linking peptidoglycan strands.

- By inhibiting PBPs, amoxicillin prevents the formation of a rigid cell wall.

- This leads to bacterial cell lysis and death.

Amoxicillin’s effectiveness against Enterococcus faecalis is variable due to resistance mechanisms. These include:

- Production of beta-lactamases, enzymes that degrade amoxicillin.

- Alterations in PBPs, reducing amoxicillin binding affinity.

- Efflux pumps, which actively remove amoxicillin from the bacterial cell.

Therefore, susceptibility testing is vital before prescribing amoxicillin for Enterococcus faecalis infections. This ensures optimal treatment and minimizes the risk of treatment failure.

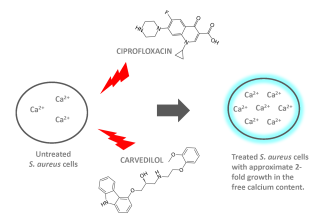

Combination therapy with other antibiotics, such as aminoglycosides, may be necessary for infections caused by amoxicillin-resistant strains. This synergistic approach enhances bacterial killing.

Enterococcus faecalis Resistance to Amoxicillin

Amoxicillin’s effectiveness against Enterococcus faecalis is significantly hampered by widespread antibiotic resistance. This resistance stems primarily from the production of beta-lactamases, enzymes that inactivate amoxicillin by breaking its beta-lactam ring.

High-level resistance often involves multiple mechanisms. These include altered penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs), which reduce amoxicillin’s binding affinity, and the presence of aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes that can also reduce the efficacy of combination therapies.

Laboratory testing is vital for determining amoxicillin susceptibility. Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values help clinicians assess resistance levels. MIC values exceeding established breakpoints indicate resistance.

Treatment options for resistant E. faecalis infections generally involve alternative antibiotics, such as ampicillin-sulbactam, vancomycin, or linezolid. Appropriate antibiotic selection requires consideration of local resistance patterns and patient-specific factors.

Infection control measures are critical in preventing the spread of resistant E. faecalis. These include meticulous hand hygiene, proper sterilization techniques, and adherence to infection prevention protocols in healthcare settings.

Ongoing surveillance of E. faecalis resistance patterns is essential for guiding antibiotic stewardship and optimizing treatment strategies. Collaboration between clinicians, microbiologists, and infection prevention specialists is vital.

Clinical Significance: Infections Caused by Amoxicillin-Resistant E. faecalis

Amoxicillin-resistant Enterococcus faecalis poses a significant clinical challenge. Infections can be severe and difficult to treat.

Common infections include:

- Urinary tract infections (UTIs): These are frequently observed, often presenting with symptoms like pain during urination and frequent urges.

- Bacteremia: Bloodstream infections can be life-threatening and require immediate intervention.

- Endocarditis: Infection of the heart valves is a particularly serious complication, often requiring surgical intervention.

- Wound infections: These infections can hinder healing and lead to prolonged hospitalization.

- Intra-abdominal infections: Infections within the abdominal cavity can be complex and require aggressive management.

Risk factors for acquiring these infections include:

- Prior antibiotic use: Extensive antibiotic exposure increases the likelihood of encountering resistant strains.

- Hospitalization: Healthcare settings are environments where resistant bacteria thrive.

- Immunocompromised status: Individuals with weakened immune systems are more susceptible to serious infections.

- Underlying medical conditions: Conditions like diabetes or chronic kidney disease can increase susceptibility.

Treatment of amoxicillin-resistant E. faecalis infections relies on alternative antibiotics. Appropriate therapy depends on susceptibility testing, identifying the most effective agent against the specific strain. Options often include:

- Ampicillin/sulbactam

- Vancomycin

- Linezolid

- Daptomycin

- Tigecycline

Early diagnosis and appropriate antimicrobial stewardship are crucial in managing these infections to reduce morbidity and mortality. Consult infectious disease specialists for complex cases.

Diagnosis of E. faecalis Infections

Confirming E. faecalis infection begins with a thorough patient history and physical examination. Focus on identifying symptoms related to the suspected infection site, such as urinary tract infections (UTIs), endocarditis, or wound infections. Detailed information about recent medical procedures, antibiotic use, and underlying health conditions is crucial.

Laboratory tests are paramount. Obtain samples from the infected site–urine for UTIs, blood cultures for endocarditis, or wound swabs–for microbiological analysis. Gram staining provides initial identification; however, definitive identification requires culturing the sample on appropriate media and performing biochemical tests to confirm the presence of E. faecalis. Antibiotic susceptibility testing is vital to guide treatment; this determines the effectiveness of various antibiotics, including amoxicillin.

For suspected endocarditis, echocardiography plays a key role in visualizing the infection’s location and extent on the heart valves. Imaging techniques such as ultrasound or CT scans can also assist in diagnosing infections at other sites.

Rapid diagnostic tests may offer quicker results but may not be as sensitive or specific as traditional culture methods. Consider these options based on the clinical context and availability of resources. Consult with infectious disease specialists for complicated cases or for infections in immunocompromised patients, ensuring optimal management.

Remember, proper diagnosis requires a multi-faceted approach combining clinical evaluation, microbiological analysis, and, when necessary, imaging techniques. Accurate diagnosis guides effective treatment, minimizing complications and improving patient outcomes.

Treatment Options Beyond Amoxicillin

If amoxicillin fails to treat your Enterococcus faecalis infection, several alternatives exist. Your doctor will consider factors like the specific strain of bacteria, your medical history, and potential drug allergies before choosing the best option.

Alternative Antibiotics

Ampicillin/sulbactam often proves effective where amoxicillin falls short. Vancomycin represents a powerful option, particularly for serious infections, but carries a higher risk of side effects. Linezolid and daptomycin are other choices, reserved for cases resistant to other antibiotics. Always discuss potential drug interactions with your physician.

Combination Therapy

Sometimes, combining antibiotics provides a synergistic effect, enhancing treatment success. Your doctor might prescribe a combination of antibiotics based on your specific situation. This approach can be particularly beneficial against resistant strains.

Surgical Intervention

Enterococcus faecalis infections sometimes necessitate surgical intervention to drain abscesses or remove infected tissue. This approach often complements antibiotic therapy, significantly improving outcomes.

Monitoring and Follow-up

Regular monitoring of your condition is key. Your physician will likely schedule follow-up appointments to assess your progress and make adjustments to your treatment plan as needed. Early detection of treatment failure allows for prompt changes, maximizing your chances of a full recovery.

Preventing E. faecalis Infections

Maintain meticulous hygiene. Wash your hands thoroughly and frequently with soap and water, especially after using the restroom and before handling food. Hand sanitizer with at least 60% alcohol is a helpful supplement.

Practice safe food handling. Cook meat to the proper internal temperature to kill bacteria. Refrigerate perishable foods promptly and avoid cross-contamination between raw and cooked foods.

Keep your surroundings clean. Regularly disinfect frequently touched surfaces, such as doorknobs, light switches, and countertops. Pay attention to areas prone to moisture, such as bathrooms and kitchens.

Boost your immune system. Eat a balanced diet rich in fruits, vegetables, and whole grains. Get adequate sleep and manage stress effectively. Consider consulting your doctor about immune-boosting supplements.

Follow medical advice carefully. Complete the full course of antibiotics prescribed by your doctor, even if you feel better before finishing. This prevents the development of antibiotic resistance.

Proper wound care is critical. Clean and cover any wounds immediately and seek medical attention for deep or infected wounds. This prevents bacteria from entering the bloodstream.

Stay hydrated. Adequate fluid intake supports your body’s natural defenses against infection.

Practice safe sex. Use condoms to reduce the risk of sexually transmitted infections, some of which can be caused by E. faecalis.

Future Directions in Combating Amoxicillin-Resistant E. faecalis

Develop novel β-lactam antibiotics that bypass existing resistance mechanisms. This involves focusing on compounds that circumvent penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs) modifications commonly seen in amoxicillin-resistant E. faecalis strains. Research into novel PBP inhibitors should be prioritized.

Explore alternative therapeutic strategies. Bacteriophage therapy, utilizing specific phages targeting E. faecalis, presents a promising avenue. Preclinical studies evaluating efficacy and safety are urgently needed. Similarly, investigate the potential of antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) with activity against resistant strains. Their broad-spectrum activity and reduced likelihood of resistance development merits investigation.

Targeting Biofilm Formation

Disrupt E. faecalis biofilm formation. Biofilms contribute significantly to antimicrobial resistance. Research should focus on compounds that effectively inhibit biofilm development or dispersal, enhancing the efficacy of existing antibiotics.

Combating Resistance Mechanisms

Develop inhibitors specifically targeting enzymes responsible for antibiotic inactivation. For example, β-lactamases are frequently implicated in amoxicillin resistance. Investigating and developing specific β-lactamase inhibitors for use in combination with amoxicillin could resensitize resistant strains.

Enhanced Diagnostics

Improve rapid diagnostic tests to quickly identify amoxicillin resistance in E. faecalis. This allows for timely adjustments to treatment strategies, minimizing treatment failures and preventing further spread of resistance.

| Strategy | Focus | Potential |

|---|---|---|

| Novel Antibiotics | Bypass PBP modifications | High |

| Phage Therapy | Specific phage targeting | Medium-High |

| AMPs | Broad-spectrum activity | Medium |

| Biofilm Disruption | Inhibit biofilm formation | High |

| β-Lactamase Inhibitors | Target enzyme inactivation | High |

| Rapid Diagnostics | Early resistance detection | High |

Combination Therapies

Investigate synergistic combinations of existing antibiotics and novel therapeutic agents. Combining amoxicillin with agents targeting different resistance mechanisms or different bacterial processes may overcome resistance and improve treatment success rates. This approach is especially crucial for managing infections with multi-drug resistant E. faecalis.